More than 700 bird species breed in North America, and their nesting behaviors are complex with significant variations among species and regions. Birds use day length as a cue to initiate breeding, timing their nesting to coincide with food abundance. The official bird nesting season in the U.S. is generally considered to run from February through July, with a peak from March to July. However, climate change has caused some species to begin nesting earlier. Birds select breeding territories that provide food, shelter, and protection, and then go through a process of courtship, nest building, egg laying, incubation, and caring for the young before the young birds fledge and leave the nest.

Key Takeaways

- North America is home to over 700 bird species with diverse nesting behaviors.

- The official bird nesting season in the U.S. typically runs from February to July, with a peak from March to July.

- Climate change has caused some bird species to begin nesting earlier than historical patterns.

- Birds select breeding territories that provide food, shelter, and protection for their young.

- The nesting process involves courtship, nest building, egg laying, incubation, and caring for the young until they fledge.

Understanding the Avian Nesting Cycle

Avian breeding habits are a fascinating and complex aspect of the natural world. The avian nesting cycle encompasses several key stages, from finding a suitable breeding territory to the successful fledging of young birds. Understanding the intricacies of this cycle is crucial for appreciating the remarkable adaptations and behaviors of our feathered friends.

The Intricacies of Bird Breeding Habits

More than 700 bird species breed in North America, each with its own unique mating rituals and nesting preferences. Birds often use day length as a trigger to determine the optimal time for breeding, with spring being the primary nesting season for many species. Female birds carefully assess potential mates, choosing partners based on their overall quality and vigor.

Despite the impression of monogamy, DNA analyses have revealed that even supposedly faithful birds may not always be sexually exclusive. Some species exhibit more complex mating behaviors, such as polygyny (one male mating with multiple females) or polyandry (one female mating with multiple males).

Variations Among Species and Regions

The duration and timing of the avian nesting cycle can vary significantly depending on the bird species and geographic region. Migratory birds must carefully time their nesting to coincide with the availability of food resources, while non-migratory species may maintain breeding territories year-round.

Factors like day length, weather patterns, and food supply can all influence when birds begin their nesting activities each year. Some beach-nesting birds, such as black skimmers and least terns, even form large colonies of hundreds or thousands of individuals to breed together.

“Birds use day length to determine the breeding season trigger, and females choose mates based on the males’ overall quality and vigor.”

The avian nesting cycle is a remarkable and complex process, shaped by the unique adaptations and behaviors of each bird species. Understanding these intricacies can provide valuable insights into the natural world and the factors that influence the breeding success of our feathered friends.

Finding a Breeding Territory

As the seasons change, birds begin preparing for the arrival of their young. Both migratory and non-migratory species engage in a crucial task: finding and defending a suitable breeding territory. This process is driven by a range of factors that influence a bird’s choice of nesting grounds.

Migratory vs. Non-Migratory Birds

Migratory birds, those that travel long distances to breed, often arrive at their breeding grounds in the spring and immediately begin the search for a territory. They use day length as a cue to initiate breeding and establish their domain. In contrast, non-migratory species may maintain a territory throughout the winter or establish a new one as the weather warms.

Factors Influencing Territory Selection

Birds select breeding territories that provide the resources necessary for successful nesting and rearing of their young. Key factors include the availability of potential nest sites, reliable food sources, and protection from predators. The habitat type, proximity to essential resources, and level of competition with other birds can all influence a bird’s territory selection.

“The size of territories varies based on individual, species, and environmental conditions, with birds that feed on animal food generally having larger territories than those feeding on plant food.”

Research has shown that the relationship between the number of breeding pairs and the area of their territories is inversely proportional. As the number of pairs increases, the territory size decreases, reflecting the need to optimize resource utilization in a limited space.

Territoriality is a complex behavior that can impact bird populations in various ways. In some cases, it may lead to increased mortality or decreased breeding success as birds are forced into suboptimal habitats due to competition. However, it also serves crucial functions, such as protecting nest sites, reducing aggression, and controlling population numbers.

Understanding the nuances of bird territory selection is essential for conservationists and birdwatchers alike, as it sheds light on the intricate behaviors and adaptations that allow these feathered creatures to thrive in diverse environments.

Courtship and Mate Selection

As the breeding season approaches, birds engage in a captivating display of avian breeding habits to attract potential mates. Females carefully assess the overall quality and vigor of prospective partners based on factors like breeding plumage, courtship displays, nest-building abilities, and food provisioning.

The formation of social pair bonds ties male and female birds together for the duration of the breeding season. However, some species exhibit more promiscuous mating strategies, with individuals having multiple mates or sharing the parental duties within a single nest.

“Courtship behaviors serve the purpose of attracting suitable mates and establishing bonds necessary for mating and raising offspring.”

During courtship, birds may exhibit a variety of behaviors, including mate-feeding, body displays, song-flight displays, tail fanning, head-jerking, dancing, and food exchanges. These rituals stimulate the necessary physical changes in birds to prepare them for the act of mating.

While some bird species form lifelong bonds that can last for decades, others may stick together for only one or a couple of breeding seasons. The diversity in courtship displays and mate selection strategies reflects the remarkable adaptations of different avian species to their unique ecological niches and evolutionary histories.

Nest Construction and Materials

Birds construct nests to provide a safe and secure environment for their eggs and young to develop. The diversity in nest styles and locations is truly remarkable, showcasing the ingenuity and adaptability of our feathered friends.

Diversity in Nest Styles and Locations

Nest styles can range from simple scrapes in the ground to intricate, woven structures. Some birds, like orioles, create stunning pendulous nests that hang from tree branches. Others, such as hummingbirds, build delicate cup-shaped nests camouflaged with moss and lichen. Nests can be found in a variety of locations, including trees, shrubs, cliff ledges, burrows, and even on human-made structures like buildings and bridges.

The materials used for nest construction are equally diverse. Birds utilize a wide array of natural elements, such as twigs, leaves, dry grass, feathers, moss, and mud, to create their homes. Some species even incorporate human-made materials like string, yarn, and dryer lint into their nests.

“Birds are masters of their craft, weaving together the perfect sanctuary for their young.”

Typically, the female bird is responsible for the majority of the nest-building, though in some species, both parents or even just the male contribute to the construction process.

- Nest construction is a crucial part of the avian breeding cycle, providing a safe and nurturing environment for eggs and hatchlings.

- The diversity in nest styles and locations showcases the adaptability and ingenuity of different bird species.

- Birds use a wide range of natural and human-made materials to build their nests, often displaying remarkable craftsmanship.

- Nest-building is typically a female-led endeavor, though in some species, both parents or just the male contribute to the construction process.

Copulation and Egg Formation

The intricate avian breeding habits involve a delicate interplay between hormonal changes and physical adaptations. As the breeding season approaches, the reproductive organs of both male and female birds undergo dramatic growth and development. This surge in hormonal activity prepares the birds for the crucial stages of copulation and egg formation.

Hormonal Changes for Breeding Readiness

The onset of the breeding season triggers a cascade of hormonal changes in birds. Hormones like testosterone, estrogen, and progesterone play a pivotal role in driving the birds’ reproductive behaviors. These hormones stimulate the growth and function of the birds’ reproductive organs, enabling them to engage in successful copulation and egg production.

During this time, the male birds’ testes can increase in size by as much as 20 times their normal volume, while the females’ ovaries and oviducts also undergo significant expansion. This physical transformation is essential for the birds to be able to effectively mate and form viable eggs.

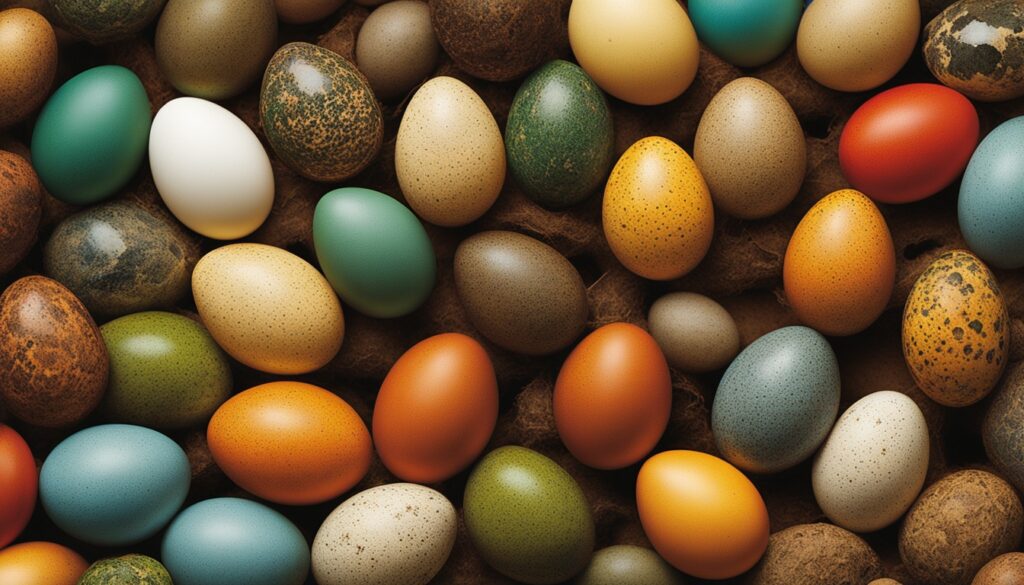

The female bird’s body then takes charge of the egg formation process. As the eggs mature, the oviduct produces the necessary materials to form the eggshell and pigments that give the eggs their distinctive coloration. This intricate process ensures that the eggs are ready for successful fertilization and eventual hatching.

“The coordination of hormonal changes and physical adaptations is crucial for birds to successfully transition through the various stages of the breeding cycle, from courtship and mating to egg-laying and chick rearing.”

By understanding the intimate details of avian breeding habits, particularly the role of hormones in copulation and egg formation, we can gain valuable insights into the remarkable reproductive strategies of these winged wonders.

Egg Laying and Clutch Size

The process of egg laying and the number of eggs a female bird lays in a single nesting attempt, known as the clutch size, are fascinating aspects of avian biology. Clutch size can vary widely across different bird species, reflecting the diverse reproductive strategies evolved to ensure the survival of their young.

On average, the clutch size across all bird species can range from as few as 1 egg to over 20 eggs. Many tropical bird species tend to lay smaller clutches of just 2-3 eggs, while waterfowl, such as ducks and geese, can lay up to 15 eggs in a single clutch. The egg-laying frequency also varies, with some birds laying eggs daily, while others may do so on a weekly basis.

Interestingly, the size, shape, color, and texture of bird eggs can also exhibit significant variations in clutch size within the same species. These variations can be influenced by factors such as food availability, weather conditions, and the female bird’s age and experience.

“The diversity of egg-laying strategies among birds is a testament to the remarkable adaptability of these flying creatures.”

Understanding the intricacies of egg laying and clutch size is crucial for gaining insights into the breeding habits and reproductive success of different bird species. This knowledge can inform conservation efforts and help us better appreciate the remarkable diversity of the avian world.

Incubation Period and Parental Roles

The incubation period is a critical stage in the nesting cycle of birds, during which the developing embryos are kept at the optimal temperature for healthy growth. The duration of incubation varies widely across different bird species, with larger birds generally requiring longer incubation times. Female songbirds typically begin incubation after the last egg is laid, while other species may start as soon as the first egg is laid.

Both male and female birds often participate in the incubation duties, taking turns to ensure the eggs are kept warm and protected. This shared responsibility between the parents is an essential aspect of avian parental roles. The level of parental care required after hatching also varies significantly between altricial and precocial bird species.

Altricial and Precocial Species

Altricial birds, such as songbirds and parrots, hatch in a relatively undeveloped state. These altricial hatchlings are helpless, blind, and require constant parental care and feeding to survive. In contrast, precocial birds, like chickens and ducks, are more advanced at hatching, able to move around and even feed themselves to a certain degree. Precocial species require less intensive parental care compared to their altricial counterparts.

The differences in the level of development at hatching significantly impact the parental roles and responsibilities of birds. Altricial species demand more time and effort from their parents to ensure the survival of their offspring, while precocial birds can become relatively independent sooner. Understanding these variations is crucial for appreciating the diverse strategies employed by birds in successfully raising their young.

incubationis a critical stage in the nesting cycle of birds, and parental roles play a vital part in the survival of altricial and precocial bird species.

“The incubation period is a critical stage in the nesting cycle of birds, during which the developing embryos are kept at the optimal temperature for healthy growth.”

Hatching and Caring for the Young

The hatching process marks a critical juncture in the avian nesting cycle, as it signals the transition from egg incubation to parental care. The way in which birds care for their young can vary greatly depending on the species. Altricial bird species, such as songbirds, are born blind, featherless, and helpless, relying entirely on their parents for warmth, protection, and a steady supply of food. In contrast, precocial birds like ducks and shorebirds are more developed at hatching, with open eyes and the ability to move and feed themselves.

Feeding Demands and Predator Risks

As the young birds grow, their parents must work tirelessly to keep up with their voracious feeding demands. This critical stage exposes both adults and nestlings to increased predator risks. Birds must balance the need to fulfill their feeding demands with the necessity to protect their vulnerable offspring from a variety of predators.

- Altricial species require constant attention and care from their parents, who must frequently return to the nest to feed their hungry chicks.

- Precocial species, while more independent, still rely on their parents for protection and guidance as they learn to navigate their environment.

- Regardless of species, the hatching and early rearing period is a vulnerable time, with both parental care and predator risks playing a crucial role in the survival of the young birds.

“The first few weeks after hatching are the most critical for a bird’s survival, as they are completely dependent on their parents for food and protection.”

As the nestlings grow and develop, their parents must make constant adjustments to ensure their safety and well-being. This delicate balance between feeding demands and predator risks is a key factor in the success of the avian nesting cycle.

when do birds stop nesting

Factors Influencing the End of Nesting Season

As summer transitions into fall, the nesting season for many bird species in the United States starts winding down. The exact timing for when birds stop nesting can vary depending on a variety of factors, but it’s generally observed to occur sometime between July and September.

One of the primary drivers for the end of nesting is the decreasing daylight hours as the seasons change. Shorter days trigger hormonal changes in birds that signal the conclusion of their breeding cycle. Additionally, the availability of food resources, especially insects and berries that are crucial for feeding nestlings, begins to diminish as autumn approaches.

Another key factor is the increasing independence of the young birds, or fledglings. As the nestlings mature and learn essential survival skills, they become less reliant on their parents’ care, allowing the adult birds to shift their focus away from nesting duties.

- Approximately 75% of bird species in the United States stop nesting by the end of August.

- On average, birds cease nesting activities 2-4 weeks before embarking on their autumn migration.

- Some species, like the American Robin, may attempt a second or even third brood if conditions remain favorable, prolonging their nesting season.

“The end of the nesting season is a natural transition, as birds prepare for the challenges of migration and winter survival.” – Dr. Avian Ecologist

While the specific when do birds stop nesting timeline can vary, the primary factors influencing end of nesting season are the changing daylight, dwindling food sources, and the young birds’ increasing independence. This seasonal shift marks an important phase in the annual cycle of many avian species.

Fledging and Leaving the Nest

As young birds reach a certain age, typically between 2-3 weeks for most songbirds and up to 8-10 weeks for larger species, they begin the process of fledging or leaving the nest. This critical transition marks a significant milestone in the avian life cycle, as fledglings embark on the journey towards independent survival.

Once they leave the nest, these young birds face a high-risk period, with more than half of first-year birds failing to navigate the challenges of young bird survival. Predators and the difficulties of finding food pose constant threats, and the fledglings must quickly learn essential survival skills to avoid becoming the prey.

The percentage of birds that successfully leave the nest and establish their independence can vary greatly among different bird species, ranging from as low as 10% to as high as 90%. This disparity is often influenced by factors such as the species’ adaptations, habitat, and parental care strategies.

The average age for fledging also differs significantly, with some species leaving the nest as early as 10 days old, while others may remain for up to 60 days. This variation is largely dependent on the altricial or precocial nature of the species, as well as the specific environmental conditions they face.

While the initial post-fledging period is undoubtedly challenging, those young birds that manage to overcome the odds have a much better chance of long-term survival. The frequency of parent birds feeding their fledglings gradually decreases over time, with an average decline of 50% after the first week, as the young birds become increasingly self-sufficient.

“The transition from the nest to independent living is one of the most perilous stages in a bird’s life, but it’s also a testament to their incredible resilience and adaptability.” – Ornithologist, Dr. Emily Graslie

Multiple Broods and Renesting Attempts

While most bird species only nest once per year, some are capable of remarkable adaptability. Species like the American Robin can have up to 4 or 5 nesting attempts in a single breeding season, a phenomenon known as multiple brooding. Birds may also attempt to renest if their first nest is destroyed, extending the overall nesting timeline. These strategies allow birds to capitalize on available food resources and better ensure the survival of their offspring, especially in the face of environmental threats.

Multiple brooding and renesting attempts are not limited to a few species. Nearly 200 bird species in Massachusetts, for instance, utilize diverse landscapes for their nesting spots, from hanging plants and building ledges to chimney cavities. Non-native species like pigeons, European Starlings, and House Sparrows have also adapted to urban environments, bringing them into potential conflict with people.

These adaptations come with both benefits and challenges. On one hand, they allow birds to adapt to changing conditions and increase their chances of successful reproduction. However, they also require additional energy expenditure and heighten the risk of nest failure or predation. Federal and state laws prohibit the disturbance of active nests, underscoring the importance of understanding and respecting these avian behaviors.

Ultimately, the ability of birds to engage in multiple broods and renesting attempts highlights their resilience and the complexity of their breeding strategies. By recognizing and accommodating these natural behaviors, we can better coexist with our feathered neighbors and ensure the continued vitality of diverse avian populations.

“It is essential to block openings in buildings to exclude birds after the young have left to prevent them from returning and starting another brood.”

Impacts of Climate Change on Nesting Timelines

Mounting evidence suggests that climate change is significantly impacting the nesting timelines of many bird species. Recent studies have revealed that compared to data from the 1960s, some birds are now beginning their breeding and nesting activities up to a month earlier.

This shift in nesting timelines is likely driven by the earlier arrival of warmer spring temperatures and increased food availability. As a result, the overall bird nesting season is getting longer in many regions, posing new challenges and opportunities for avian populations.

Long-term datasets indicate that many North American bird species have shifted their winter and breeding ranges northward over time. At least 70 bird species of subtropical, tropical, and desert areas have extended their breeding ranges north or eastward in recent decades.

A 2020 study found that resident species in eastern North America have stable ranges, while migratory birds are breeding farther north with an arrival in North America occurring about two days earlier each decade since the 1990s. Research shows that birds’ bodies are getting smaller and their wings longer as global temperatures rise.

The impacts of climate change on nesting timelines are multifaceted. Intense droughts and frequent wildfires driven by global warming can alter and destroy bird nesting areas and habitats. Species like Saltmarsh Sparrows are at risk of extinction due to sea-level rise drowning their nests in marsh grass.

Furthermore, climate change leads to new interactions among species, such as elk consuming montane plant communities, leading to declines in songbird populations. Birds also face timing mismatches, as seasonal food resources may not align with their migration schedules, affecting breeding success.

Combatting non-climate threats, reducing carbon emissions, and restoring bird habitats are suggested ways to help birds as climate changes. With the impacts of climate change on nesting timelines becoming increasingly evident, it is crucial to understand and address these challenges to protect avian populations for the future.

“By the year 2050, 15–37% of existing animal and plant species on Earth are predicted to become extinct. Half of all species on Earth may experience extinction by 2100.”

Conclusion

The avian nesting cycle is a complex and fascinating process, with significant variations in behaviors and timelines across different bird species and geographic regions. Understanding the intricacies of when birds start and stop nesting, as well as the factors influencing their breeding habits, is crucial for effectively managing and conserving bird populations.

As climate change continues to impact nesting patterns, ongoing research and monitoring will be essential for adapting our approaches to support the health and resilience of bird communities. From recognizing anti-predator behaviors to providing suitable nesting sites and resources, our collective efforts can make a real difference in protecting these remarkable winged creatures during their most vulnerable stages of life.

By staying informed about the avian nesting cycle and being mindful of our actions during the breeding season, we can foster a deeper appreciation for the fascinating world of birds and contribute to their long-term survival. As we continue to explore the complexities of avian breeding habits, we can uncover new insights that will guide us in our mission to coexist harmoniously with these feathered denizens of our shared natural landscapes.

FAQ

What is the typical bird nesting season in the United States?

The official bird nesting season in the U.S. is generally considered to run from February through July, with a peak from March to July. However, climate change has caused some species to begin nesting earlier.

How do birds select their breeding territories?

Birds use day length as a cue to initiate breeding and establish a territory. Good breeding territories provide potential nest sites, reliable food sources, and protection from predators. Factors like habitat, proximity to resources, and competition with other birds influence which territories birds select.

What are the key stages of the avian nesting cycle?

The avian nesting cycle consists of several key stages, including finding a breeding territory, courtship and mate selection, nest construction, egg laying and incubation, hatching and caring for the young, and fledging.

How do birds construct their nests?

Nest styles and materials vary widely by species, ranging from simple scrapes in the ground to intricate structures built from natural and human-made materials. Nests can be found in trees, on cliff ledges, in burrows, on human-made structures, and many other locations.

How do birds incubate their eggs?

Birds incubate their eggs to maintain the proper temperature for embryonic development. Both male and female birds may participate in incubation duties, and the incubation period varies by species.

What happens when the young birds hatch?

Altricial bird species, such as songbirds, are born blind, featherless, and helpless, relying on their parents for warmth, protection, and food. Precocial birds like ducks and shorebirds are more developed at hatching, with open eyes and the ability to move and feed themselves.

When do birds stop nesting?

The end of the bird nesting season can vary by species and location, but is generally considered to occur sometime between July and September in the United States. Factors like decreasing daylight, food availability, and the young birds’ increasing independence influence when birds stop nesting and caring for their offspring.

How do climate change and other environmental factors affect bird nesting patterns?

Recent studies have shown that climate change is impacting the nesting seasons of many bird species, causing them to begin breeding and nesting earlier than they have in the past. This shift in nesting timelines is likely driven by the earlier arrival of warmer spring temperatures and increased food availability.

It’s great that you are getting ideas from this paragraph

as well as from our argument made at this place.

Feel free to visit my site :: nordvpn coupons inspiresensation (ourl.in)

nordvpn 350fairfax

I enjoy looking through an article that will make

people think. Also, many thanks for allowing for me

to comment!

Also visit my web page – nord vpn promo